M is for Microraptor and a Moth on a Misty, Moonlit night…

The full moon is always a lovely sight to behold, especially when it gets that blue glow around it. This time of year always brings some particularly spectacular sightings. My favorite is when it rises just as the last light of the setting sun makes it look huge and orange in the sky.

Did dinosaurs ever look up at the moon in wonder?

Once upon a time, the moon was much closer to the Earth, and it has been slowly drifting further away each year. The same gravity that keeps the moon in its orbit around Earth is also gradually pushing it away with momentum, just like being on the outside of one of those merry-go-rounds on the school playground. Remember those? If you were a more adventurous risk taker, you’d cling to the bars along the outer edge, and sometimes it would spin fast enough that it felt like you’d be thrown off.

This is what is, very slowly, happening to the moon, so that it would’ve been closer to Earth in the Cretaceous when Microraptor looked up at the sky. Would it be as big as it is shown to be in some scifi time-travel shows? Most likely not. If we were to go back in time and see the same moon as Microraptor in Early Cretaceous China, it would only be a tiny bit bigger than it is today. A small enough difference that it might just be a trick of the light, or the same illusion as a “harvest moon.”

The moon today is always the same size, but any appearance of being larger or smaller is all a trick on our eyes, depending on what is in the sky with it.

But would Microraptor see it?

Some have proposed that Microraptor, a pigeon-sized dinosaur famous for its four wings, was nocturnal (active at night) because of its large eyes. But more recent studies show that Microraptor had shiny, black, iridescent feathers like modern starlings and grackles, which gives them a blue or purple sheen. Like the colors you might see in an oil slick on water, or a bubble.

These colors would be very strange for an animal that was active at night, so it’s more likely that Microraptor would be sleeping when the moon came out.

This little Microraptor has woken up from its slumber because the moon is so very bright tonight, and maybe the moth flew in its face and disturbed its rest!

This moth does not belong here anyway, since it is based on a fossil from Jurassic China- Mesokristensenia trichophora. It is known from only one fossil of a tiny female about 5 millimeters long.

Speaking of moths, I recently discovered at least one reason why they are so attracted to light! Below is a video of some moths flying around a light in slow motion, and you can see that their back is turned towards the light.

Part of the reason they fly around a light is because the light of the moon or sun tells their bodies which way is up. The moon is high in the sky, so they keep their back to the moon and their faces down to the ground, but when they pass by a candle or a street light, it is brighter than the moon, so they turn their backs to the light to be “right side up”.

Since it’s a reflex, not a choice, they just can’t help but try and fly “upright”, which leads to them flying in circles with their back to the light.

But let’s get back to Microraptor.

Why did they have iridescent feathers? Why did they have four wings? Could they fly or were they stuck just gliding?

If they had iridescent feathers, that definitely seems to support a daytime lifestyle. And pretty colors and feathers are always good for showing off. Fancy feathers that make flying difficult are also very good for showing off. Think of peacocks or birds of paradise, there are many birds with outlandish-looking feathers that make it difficult, and sometimes temporarily impossible, to fly.

As to whether or not Microraptor could fly…that is a debate argued by paleontologists much more knowledgeable on the subject than me, but take a close look at the feathers on both the wings and the legs. I can’t imagine how those wouldn’t be used for flight in some way, even if it was just short bursts.

The shape of a feather is very specific, and the feathers on chickens with feathered feet have a very different shape from actual flight feathers. They look like oddly-shaped fur, not like wings.

So the fact that Microraptor had four wings is a very specific and special thing, and many believe it was capable of at least short bursts of powered flight. Perhaps even better than Archaeopteryx!

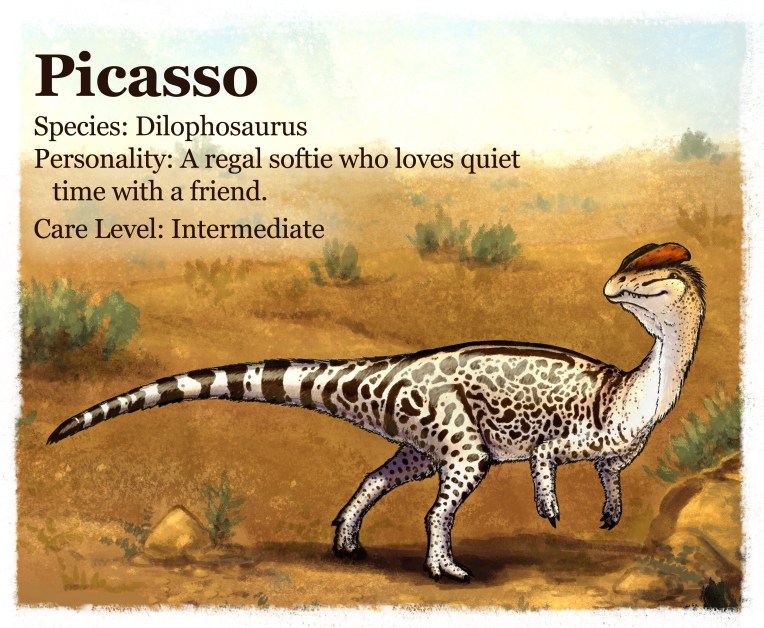

The Critter of the Month!

On the subject of fancy feathers and their many uses, here is Picasso the Dilophosaurus, from Early Jurassic North America!

Picasso’s feathers are pure speculation. It assumes that the earliest dinosaurs started out fuzzy. Many dinosaurs, and their close cousins the flying pterosaurs, had fuzzy feathers. With that in mind it’s easier to assume that they are related and the common ancestors of both were fuzzy. Much easier for one group to grow feathery fluff once and lose it later, than to grow it two separate times in different groups that are completely unrelated. This is especially true for animals that have hugely different lifestyles and live in many different habitats.

So why not assume Dilophosaurus had already lost the fluff, when it’s clearly much bigger than tiny dinos that we assume would need fluff for regulating body temperature? Well, aside from the simple fact that I love the idea of a big fluffy Dilo, there are more scientific reasons.

One, look at similar-sized birds in very hot climates. Clearly feathers are an advantage and simply getting bigger is not enough to loose them for the sake of pure scales or wrinkly skin. Nor is living somewhere hot. Also, we have some hints of possible feathers on other dinosaurs of similar size and not too distant in time. It’s not a lot to go on, but without feather impressions for Dilophosaurus itself there truly is no way to know.

Birds have a lot of variation in their feathers if you look closely, and I looked at a lot of large, ground dwelling birds in very hot climates for inspiration. What I found was very interesting. Ostriches do not have naked necks, as is often seen in cartoons, but have a fine layer of downy feathers. Emus have even more feather coverage and live in an equally hot and dry environment. It’s like wearing a sunhat and long-sleeved cotton shirt when working in the hot sun. An extra layer can actually be cooling rather than hot, because it protects the skin from the direct heat of the sun, yet still allows air to flow past. It’s also good for avoiding sunburn.

If an animal has naked skin exposed to the sun, like a vulture or naked-neck chicken, then the skin is often the same wrinkled, carunkled, flappy texture of their wattles (if they have them). The extra surface area of the skin flaps, wrinkles, or bumps, and lots of blood vessels close to the surface, help cool hot blood in the same way an air conditioner cycles warm air for cool air. The blood so close to the surface is a big reason why wattles are often red. Emus and ostriches have scaly or bare skin on the legs and underside of their wings.

So here I have Dilophosaurus with a shaggy coat of primitive feathers that help keep off the sun. Lighter feathers on the neck and tail for the breeziest sun-protection. Scales to protect the feet and legs from rocks and prickly plants. The large crest is light and strong, like a hornbill’s crest, and works double-duty as a way to keep cool, an attractive sign to potential mates, and perhaps even useful for shoving contests.

One of these days I’ll update Picasso to reflect this updated version of him…but for now I hope you enjoy seeing his classic look! Thank you so much for stopping by!

See you October 1st for the next Critter of the Month!

This critter may look all tough and prickly on the outside, but all she wants is a warm hug. 🙂

Share your guess in the comments! She’ll be one of the critters over on the critter page. 🙂