Day #23 on our Christmas Countdown is…

Wannanosaurus!

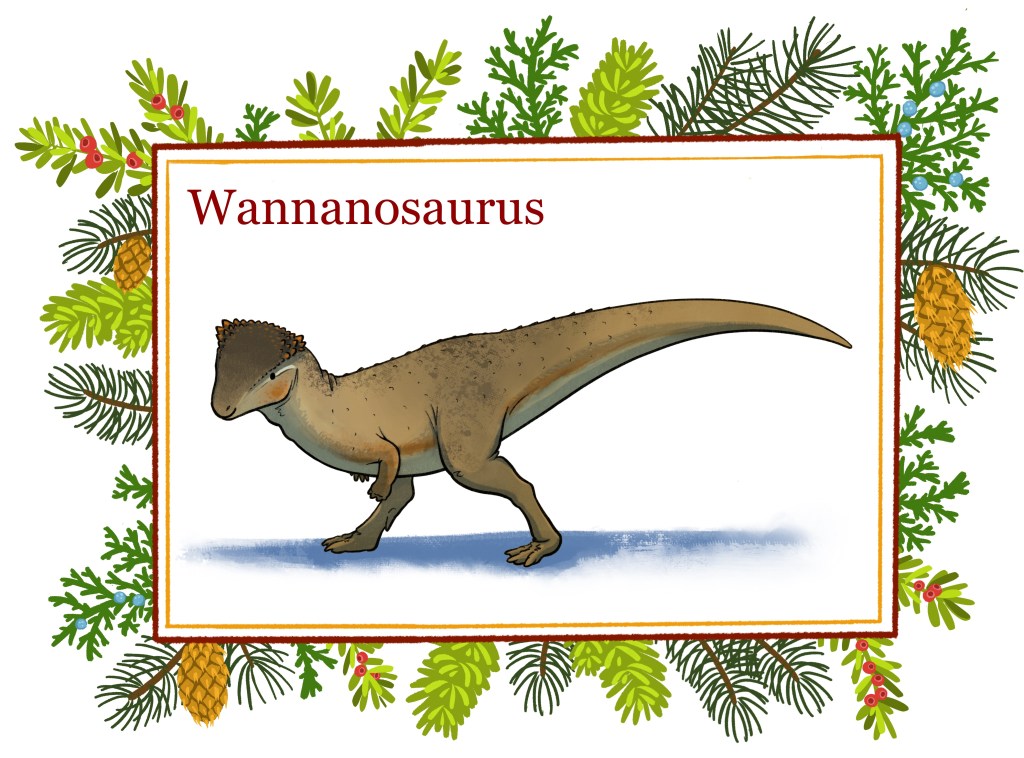

Wannanosaurus: the “Lizard from Wannan”

Wannanosaurus was a tiny relative of Pachycephalosaurus that lived in Late Cretaceous China.

Not very much is known about it except that it was most likely an adult when it died, even though it was only about two feet long from nose to tail-tip!

How does one tell if an animal is fully grown or not?

There are certain parts of the body that we think of as solid, that actually start out as separate pieces when the creature is very young.

Take human babies for example…a stereotypical skull is usually drawn as a solid piece, but a baby’s skull is divided into separate pieces. This makes it so that the head can mold to the shape of the mother’s pelvis (the “ring” of bone the legs connect to at the hips), and slide out more easily when it’s time to be born.

If you get the chance to hold a baby that’s under a year old, you may notice a soft spot on the top of the head. There are two of these “soft spots,” called fontanelles, and they are actually gaps in the bone between the different sections of the skull. One on top of the head, and another in the back.

Over time as the baby grows, the bone grows to close these gaps, until at last they meet and form “sutures.” There is some very slight movement still possible in these thin joints between the sections of the skull, but they are basically considered immobile.

Of course, baby dinosaurs don’t have to mold their skulls to be born. So why do their bones tell the story of their age?

Like humans and most other back-boned animals, growing dinosaurs first develop a skeleton made of cartilage. Cartilage is strong and flexible, which is great if your life starts out crammed inside an egg or other tight space. Cartilage is also one of the first steps to growing bones because the cartilage can become bone, or ossify.

As you might imagine, certain areas are going to ossify before others. This is partly because there are two ways that bone is formed in the body, and one of the two is faster than the other. The second reason is that many bones need to be able to grow longer and larger as the animal matures.

This is possible with cartilage and the formation of “growth plates.”

In short, certain parts of the body that must continue growing very quickly, like the skull or leg bones, are a good way to tell if the animal is still young.

For Wannanosaurus, all the bones found appear to be “fused,” like what one would see in an adult. So the animal must be an adult even though it’s very small.

This is a big reason why dinosaurs like Stygimoloch and Dracorex were discovered to be growth stages of Pachycephalosaurus, and not unique genera on their own. But what if we only have a few fossils of a dinosaur, and simply don’t have an adult of it yet?

This is an interesting question, because there is never a guarantee we will ever find more fossils of a particular animal, and we need some way to catalog it as something separate from everything else. At least if there is enough to make it different from every other fossil animal we know about. This keeps things organized so that new fossils can be compared to old ones.

Do you think fossils of dinosaurs only known from young animals should be named? What if, like Dracorex, we lose a truly epic name because it turns out that animal is in a younger growth stage than another animal?

I must say I do miss the fact that Dracorex hogwartsia is not a genus in its own right (in a nostalgic, wistful kind of way), and some are upset about Nanotyrannus. I’d love to hear your opinion in the comments!

See you tomorrow for day 24 of the Critter Christmas Countdown!

So glad you covered another marginocephalian, and you do make a good point on determining whether a specimen is a growth stage or a separate species. Speaking of these two topics, young Prenocephale and Torosaurus specimens have been found, determining that Homalocephale and Triceratops are separate from each respectively.

For today, I would like to dedicate to Materpiscis, a placoderm fish from the Late Devonian of Australia. Known from the Gogo Formation within the state of Western Australia, the only known specimen of this fish has an unborn embryo present inside the mother, with the preservation of an umbilical cord, making Materpiscis the oldest known vertebrate to show the act of giving birth to live young.

Found in 2005, the fish would have been about 11 inches (28 cm) long and had tooth plates to grind up prey. Placoderms are known for having armored tooth plates, and Materpiscis was no exception, with it likely using its plates to crush shellfish and corals.

Here are my headcanon names for each, by the way:

Wannanosaurus: Wanda

Materpiscis: Madeline (if a juvenile will also be part of the gallery, then my headcanon name for it is Maddie)

LikeLike

Aw cutie, also I don’t really trust Jack Horner much, as he has been known to disregard evidence that doesn’t support his claims. That is until he can’t anymore, for example the T-Rex is a Scavenger not a hunter theory

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, when ever you get the chance, (take your time, I’m in no hurry) you might want to check the new study from this year

LikeLiked by 1 person

I find it kind of funny that there even is a debate on T. rex as scavenger vs. hunter. Just look at hyenas or any other predator. Carnivores will take any opportunity for an easy meal, especially during times of scarcity, so any “predator” can turn scavenger should the opportunity or necessity arise. Hyenas have been known to actively hunt as well. If a critter is hungry, it will find food, and sometimes there isn’t a convenient carcass, and other times hunting goes poorly. *shrug* Nature rarely has hard rules on this sort of thing.

I would love to check out the latest study. What is it called? If you wouldn’t mind sharing a link that would be great. 🙂

LikeLike